A common acronym being discussed more and more in fair lending circles is REMA. The goal of this article is to establish a better understanding of what REMA is and how it can impact your bank.

REMA is defined as the Reasonable Expected Market Area, which is the geographical area the regulatory agency believes a bank can serve based on the bank’s distribution of applications and loan originations and its marketing and outreach efforts. In other words, where the bank is actually marketing and providing credit and where it could reasonably be expected to have marketed and provided credit.

REMAs are used in redlining analyses by the regulatory agencies when conducting fair lending reviews. Most regulatory agencies will use the term REMA; however, the Federal Reserve Board performs a similar analysis, but uses the term Credit Market Area (CMA). For the remainder of this article, TCA will refer to these areas as REMA.

Remember, the definition of redlining is a form of illegal disparate treatment in which a lender provides unequal access to credit, or unequal terms, because of the race, color, national origin, or other prohibited characteristics of the residents of the area in which the credit seeker resides or will reside or in which the residential property to be mortgaged is located. A bank’s REMA can be the same as a bank’s Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) assessment area, but it can also be different. A bank may determine its REMA for review and analysis purposes, but the regulatory agencies may define a bank’s REMA altogether differently. REMA is viewed in a very subjective manner. You really don’t want the agency determining your REMA and you don’t want an examination to be the first time you hear of all this.

Several factors are taken into consideration when REMA is determined:

- Branch locations along with history of openings, closures, and relocations;

- History of mergers and acquisitions;

- The defined market area noted in the bank’s policies;

- Advertising and marketing programs;

- Locations of loan applications;

- Locations of loan originations; and

- Locations of substantially minority census tracts (or low- and moderate- income census tracts) of the bank’s assessment area or REMA.

As a bank, be sure you can define your REMA, your reasoning for the definition of the bank’s REMA and business decisions that went into that definition. A well-developed REMA description and understanding of the bank’s lending patterns in the REMA and comparative analysis of peer banks will ensure knowledgeable and effective conversation with your examiner when a fair lending review is being conducted at your bank. The last thing you want is a lack of REMA information when confronted by examiners quoting that your bank is significantly lower than the REMA peers.

A good way to avoid surprises in your REMA definition, especially if your bank has a great working relationship with your regulatory agency, is to reach out to them for a discussion about the bank’s REMA. As you present your information, the agency can let you know whether or not you are on track.

When considering and developing your REMA, mapping is a great tool to see where the bank’s loan applications and originations are and how that relates to the bank’s branch network and current assessment area. Looking at the map will show all the loans being made outside a bank’s REMA/assessment area. If a large number of loans made outside the area are noted, then that area should be evaluated and considered a part of the bank’s REMA.

A best practice is to understand what your lending patterns are within the REMA. Questions to ask include:

- What does the area look like?

- Are there substantially minority population census tracts that are being unintentionally avoided?

- Could the bank have the appearance of redlining?

- What are the reasons for the results?

- Is there a lender always lending outside the assessment area?

- Are other lenders offering specialized loans (e.g., FHA), or are secondary market sellers?

- What impact could loan production offices have on the bank’s market area?

Remember, unintentional or no lending penetration that appears to be disproportionate in minority areas can be viewed as redlining.

The examiners will have already performed their analysis prior to the beginning of the examination and will expand their review when disproportionate lending patterns are identified within the REMA. The examiners will give the bank the opportunity to address the results. It is critical to be able to demonstrate your own monitoring efforts and the actions taken as the result of that analysis. If the bank has self-identified this risk and started to take active corrective measures with acceptable ongoing monitoring, it’s likely to bode well for the bank. If the bank is unaware of its lending patterns and cannot rebut or explain the disparity through an effective description of its business decision process, a MIRA or MRA may be in your consumer affairs report.

Normally, HMDA reportable loan data is utilized for the analysis due to the availability of HMDA Peer Aggregate data for peer analysis. TCA recommends that banks geocode all their loans to assist with mapping all loan products to determine whether the credit needs are being met in the substantially minority population census tracts in or reasonably expected to be in their market area. These census tracts have minority populations of 50% or greater.

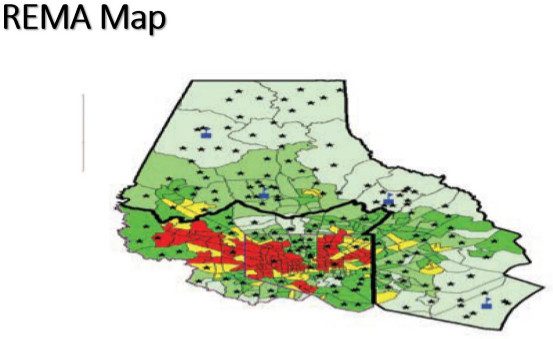

As shown in the map below, the bold black outline is the bank’s assessment area. The bank is only taking part of a county, as opposed to the whole county. This may be acceptable in some cases, but without specific analysis and barriers to the contrary, and a countywide marketing footprint, whole counties should be included within an assessment area. The census tracts in yellow and red are substantially minority population census tracts. The star symbols are loan originations.

As shown, there are a lot of originations outside the assessment area. This dispersion gives the appearance of redlining by the bank for not including the minority census tracts. In addition, there are substantial originations occurring outside the assessment area which now would be considered the bank’s REMA. The map also shows that the bank may even be redlining within the REMA. Corrective action would need to be made immediately upon this self-discovery.

Let’s look at the actual case that reinforces the validity of our supposition. The Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a lawsuit against KleinBank for violating the Fair Housing Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which prohibits financial institutions from discriminating on the basis of race and color in their mortgage lending practices. The lawsuit alleged that from 2010 to 2015, the bank structured its residential mortgage lending business in such a way as to avoid serving the credit needs of neighborhoods where a majority of the residents are racial and ethnic minorities. The DOJ pressed redlining discrimination.

The bank’s alleged redlining practices included:

- Excluding majority-minority neighborhoods from the area it serves;

- Locating branch offices and mortgage offices in majority non-minority neighborhoods, but not in minority majority neighborhoods;

- Targeting marketing and advertising exclusively toward residents of majority-white neighborhoods;

- From 2010 to 2015, comparable lenders generated applications in the majority minority neighborhoods at over five times the rate of KleinBank; and

- Originated loans in majority minority neighborhoods at over four times the rate of KleinBank.

KleinBank reached a settlement with the DOJ for dismissal of the lawsuit to include:

- Opening one full-service brick and mortar office within a majority-minority census tract within Hennepin county;

- Continuing to develop partnerships with community organizations to help establish a presence in majority-minority census tracts in Hennepin County;

- Employing a full-time Community Development Officer who is a member of management to oversee the development of the bank’s lending in majority-minority census tracts in Hennepin County;

- Spending a minimum of $300,000 on advertising, outreach, education and credit repair initiatives over the next three years;

- Providing at least two outreach programs annually for real estate brokers and agents, developers, and public or private entities already engaged in residential and real estate-related business in majority-minority census tracts in Hennepin County to inform them of the products offered by KleinBank; and

- Investing a minimum of $300,000 over three years in a special-purpose credit program that will offer residents of majority-minority census tracts in Hennepin County home mortgage and home improvement loans on a more affordable basis than otherwise available from KleinBank, with such more affordable terms to be provided through one or more of the following means:

- Originating or brokering a loan at an interest rate that is at least ½ of a percentage point (50 basis points) below the otherwise prevailing rate;

- Providing a direct grant or portion of the loan amount for the purpose of down payment assistance, up to a maximum of 3.5 percent;

- Providing closing cost assistance in the form of a direct grant of a minimum of $500 and a maximum of 1,500;

- Paying the initial mortgage insurance premium on loans subject to mortgage insurance; and

- Using other means approved by the DOJ.

The actions of KleinBank not only cost the bank its deteriorating reputation but hit the bottom line of the bank’s profitability. Within 18 months, KleinBank was sold and most “industry watchers” believed the fair lending litigation accelerated the sale.

Just think: If the bank had taken a proactive approach in understanding its lending patterns and what its REMA may have been or what the regulatory agencies may perceive the REMA to be, the formal actions may not have been levied.

If you need help with identifying your REMA or help with fair lending risk review, please contact TCA to discuss your needs. We are here to help!